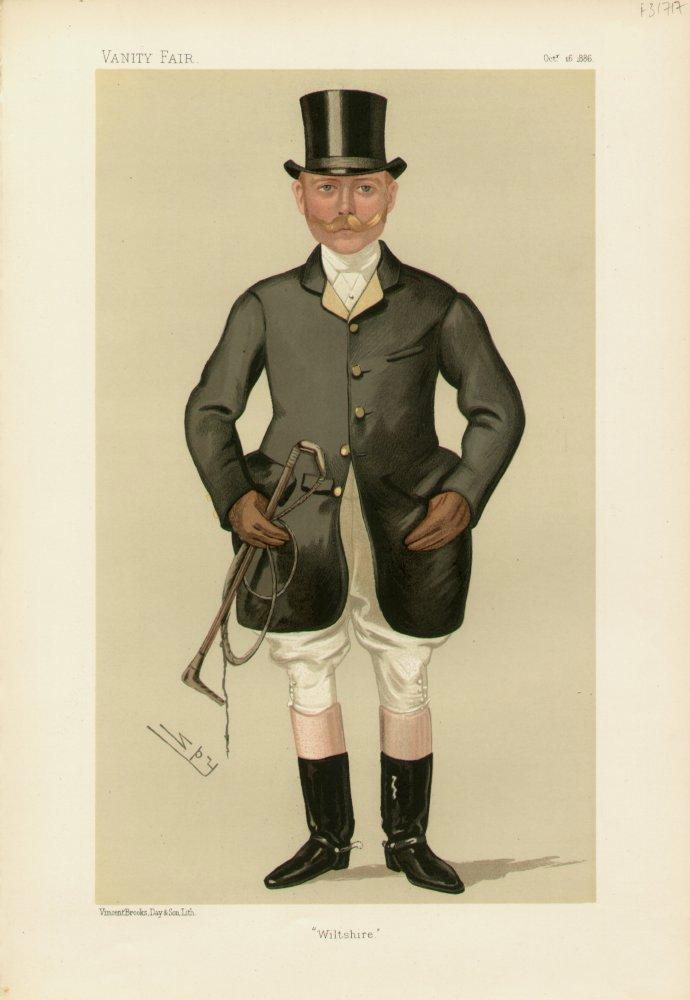

Walter Long, 1st Viscount Long on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Walter Hume Long, 1st Viscount Long, (13 July 1854 – 26 September 1924), was a British Unionist politician. In a political career spanning over 40 years, he held office as President of the Board of Agriculture,

Long won his seat with a reduced majority of 95 votes at the November 1885 general election. There was considerable anger at the Conservatives 'Fair Trade policy' for workers. He believed English people had little understanding of Ireland or the minority in Ireland that

Long won his seat with a reduced majority of 95 votes at the November 1885 general election. There was considerable anger at the Conservatives 'Fair Trade policy' for workers. He believed English people had little understanding of Ireland or the minority in Ireland that

Inheriting the Earth: The Long Family's 500 Year Reign in Wiltshire; Cheryl Nicol

at longfamilyofwiltshire.webs.com

Photograph in the National Portrait Gallery

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Long, Walter Hume 1854 births 1924 deaths People educated at Harrow School Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford Long, Walter Hume, 1st Viscount Long Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies First Lords of the Admiralty Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Dublin constituencies (1801–1922) British Secretaries of State Irish Unionist Party MPs Irish Anglicans UK MPs 1880–1885 UK MPs 1885–1886 UK MPs 1886–1892 UK MPs 1892–1895 UK MPs 1895–1900 UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs who were granted peerages Deputy Lieutenants of Wiltshire Lord-Lieutenants of Wiltshire Presidents of the Marylebone Cricket Club

President of the Local Government Board The President of the Local Government Board was a ministerial post, frequently a Cabinet position, in the United Kingdom, established in 1871. The Local Government Board itself was established in 1871 and took over supervisory functions from the ...

, Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant", from the early 19th century un ...

, Secretary of State for the Colonies

The secretary of state for the colonies or colonial secretary was the Cabinet of the United Kingdom, British Cabinet government minister, minister in charge of managing the United Kingdom's various British Empire, colonial dependencies.

Histor ...

and First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

. He is also remembered for his links with Irish Unionism

Unionism is a political tradition on the island of Ireland that favours political union with Great Britain and professes loyalty to the United Kingdom, British Monarchy of the United Kingdom, Crown and Constitution of the United Kingdom, cons ...

, and served as Leader of the Irish Unionist Party in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

from 1906 to 1910.

Background and education

Long was born at Bath, the eldest son ofRichard Penruddocke Long

Richard Penruddocke Long JP, DL (19 December 1825 – 16 February 1875) was an English landowner and Conservative Party politician. He was a founding member of the amateur cricket club I Zingari. Long was appointed High Sheriff of Montgomerysh ...

, by his wife Charlotte Anna, daughter of William Wentworth FitzWilliam Dick

The Rt Hon. William Wentworth FitzWilliam Dick (28 October 1805 – 15 September 1892), known as William Wentworth FitzWilliam Hume until 1864, was an Irish Conservative politician.

He was elected as one of the two Members of Parliament for ...

(originally Hume). The 1st Baron Gisborough was his younger brother. On his father's side he was descended from an old family of Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

gentry, and on his mother's side from Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

gentry in County Wicklow

County Wicklow ( ; ga, Contae Chill Mhantáin ) is a county in Ireland. The last of the traditional 32 counties, having been formed as late as 1606, it is part of the Eastern and Midland Region and the province of Leinster. It is bordered by t ...

. When young, Walter lived at Dolforgan Hall, Montgomeryshire

Montgomeryshire, also known as ''Maldwyn'' ( cy, Sir Drefaldwyn meaning "the Shire of Baldwin's town"), is one of thirteen historic counties of Wales, historic counties and a former administrative county of Wales. It is named after its county tow ...

, a property owned by his grandfather. Whilst living there, his father inherited the Rood Ashton Estate.

Long went to Hilperton school, Amesbury

Amesbury () is a town and civil parish in Wiltshire, England. It is known for the prehistoric monument of Stonehenge which is within the parish. The town is claimed to be the oldest occupied settlement in Great Britain, having been first settle ...

, where he was harshly disciplined by Edwin Meyrick. At Harrow, Walter was popular, proving a sporty captain of cricket. It was during Walter's studies at Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniqu ...

, that his father had a mental breakdown, and two years later died in February 1875. Upon his father's death, he took over management of the family properties, whilst his mother moved into a house in Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. It was a stressful time, during which he was frequently summoned by his mother, and his younger brother also accumulated gathering debts.

Long continued to box, ride and hunt, as well as play college cricket. Afternoons spent with the Bicester, Heythrops, and South Oxfordshire hunts were matched by the university Drag Hunt. His proficiency was reflected in the early offer to become Master of the Vale of White Horse Hunt

The Vale of the White Horse Hunt (or V.W.H.) is a fox hunting pack that was formed in 1832. It takes its name from the neighbouring Vale of White Horse district, which includes a Bronze Age horse hill carving at Uffington.

The original country ...

, which he turned down. His agent H Medlicott despaired at the danger to the family fortune, urging him to cut his relations loose; but he raised a new £30,000 mortgage on lands, which Medlicott complained he would have to sell.

Long served as an officer in the Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry

The Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry (RWY) was a Yeomanry regiment of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the United Kingdom established in 1794. It was disbanded as an independent Army Reserve (United Kingdom), Territorial Army unit in 1967, a time when t ...

, being promoted Major in 1890 and becoming Lieutenant-Colonel in command from 1898 to 1906.

Political career, 1880–1911

Long was determined on a career in politics, campaigning atMarlborough

Marlborough may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Marlborough, Wiltshire, England

** Marlborough College, public school

* Marlborough School, Woodstock in Oxfordshire, England

* The Marlborough Science Academy in Hertfordshire, England

Austral ...

in a traditional Liberal seat in 1879. After Sir George Jenkinson agreed to resign in North Wiltshire

North Wiltshire was a local government district in Wiltshire, England, formed on 1 April 1974, by a merger of the municipal boroughs of Calne, Chippenham, and Malmesbury along with Calne and Chippenham Rural District, Cricklade and Wootton Bas ...

, he was adopted by 'half a dozen country gentlemen'. At the 1880 general election, Long was elected to parliament as a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

for North Wiltshire, a seat he held until 1885. A supporter of Lord Beaconsfield

Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, (21 December 1804 – 19 April 1881) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who twice served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. He played a centr ...

, the British Empire, Church of England and state, he was against extending education, but favoured bible teachings in schools. He won the two-member North Wiltshire seat by more than 2000 votes. At the time Beaconsfield died on 19 April 1881, he was making a record of his days in the Commons: "I rose somewhere about 8.30 and as a new member was duly called". The Liberal government was in trouble over Egypt and the Bradlaugh incident; and the Conservatives were internally divided. He hunted for the Beaufort Hounds. I selected as my time, midnight until, if necessary, eight in the morning. I used to leave London at 5.30 in the morning, providing the House was up, take the train down toHe made his first speech on 26 July 1880 during the third reading of the Compensation for Disturbances (Ireland) bill.Chippenham Chippenham is a market town A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village ..., have my hunt, and get back to London by train leaving Chippenham about 7.30 … I was at the House at midnight and I would stay there till it rose.

Long won his seat with a reduced majority of 95 votes at the November 1885 general election. There was considerable anger at the Conservatives 'Fair Trade policy' for workers. He believed English people had little understanding of Ireland or the minority in Ireland that

Long won his seat with a reduced majority of 95 votes at the November 1885 general election. There was considerable anger at the Conservatives 'Fair Trade policy' for workers. He believed English people had little understanding of Ireland or the minority in Ireland that Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

would not protect, and that Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

's Home Rule policy would lead to the dismemberment of the empire. The home rule policy was defeated, Long was returned with an increased majority of 1726 votes in July 1886. Aged thirty-two, Long was asked to become a junior minister to C. T. Ritchie at the Local Government Board, in Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

's government. They had noticed his unswerving support from the backbenches. He was approachable and had a no-nonsense manner, an excellent memory: logical and crisp. He was both mature and responsible for a young MP. The very strong connections he had with the agricultural community assisted local government in his area. He entered government for the first time in 1886 in Lord Salisbury's second administration as Parliamentary Secretary to the Local Government Board

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

, serving under Charles Ritchie, and became one of the architects of the Local Government Act 1888

Local may refer to:

Geography and transportation

* Local (train), a train serving local traffic demand

* Local, Missouri, a community in the United States

* Local government, a form of public administration, usually the lowest tier of administrat ...

, which established elected county councils.

Long dealt with Poor Law reform in the county areas, slum reforms, reform of the London County Council

London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today kno ...

, and better housing for the working-classes. He was deputed to make speeches backing the government position on the LCC bill, although he was not responsible for its draft or passage. Ritchie was to deal with the towns in Local Government Act 1888, but was ill for the period, and Long had "a sound grasp its details and essentials." On 6 Feb 1887, he made an important speech in the "Plan of Campaign" from which unionism there seemed to encourage landlordism

Concentration of land ownership refers to the ownership of land in a particular area by a small number of people or organizations. It is sometimes defined as additional concentration beyond that which produces optimally efficient land use.

Distri ...

. However behind the law for tenant compensation, Long knew lay a deeper demand for independence. He continued to be worried by the Liberals' policy of Home Rule, supporting the Irish Unionists who opposed it. He could not square the retention of Irish MPs at Westminster under the scheme for the second home rule bill. Irish MPs could control English, Scottish, and Welsh affairs, so he argued. The issue was central to the general election of 1892. Long had returned from Canada on a tour speaking on the federal system there. He reiterated the claim that Ulster Unionists would never accept the bill. But Liberals argued that the Conservatives would raise bread prices, and lower wages if returned, "the labourers are ignorant lot and swallowed it whole", he decried. Long was defeated by 138 votes, losing his seat. In July 1892, Liverpool West Derby

Liverpool, West Derby is a List of United Kingdom Parliament constituencies, constituency represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, UK Parliament since 2019 by Ian Byrne ...

became vacant and Long defeated the Liberal candidate by 1357 votes at the by-election of 1893. Knowing his grasp of parliamentary procedure, Arthur James Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, (, ; 25 July 184819 March 1930), also known as Lord Balfour, was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As foreign secretary in the ...

hired him to be a strategist in opposition. The Liberals appointed Long to the Royal Commission on Agriculture, meeting at Trowbridge

Trowbridge ( ) is the county town of Wiltshire, England, on the River Biss in the west of the county. It is near the border with Somerset and lies southeast of Bath, 31 miles (49 km) southwest of Swindon and 20 miles (32 km) southe ...

on 18 January 1893.

Long continued in connections with Ireland throughout his career. He did not wish to sever legislative ties of Union with Ireland; but only to offer "an extension of the privileges of local government to the Irish people". Home Rule was thrown out by the Lords on 8 September 1893, by 419 votes to 41. In June 1895, the Liberals were resoundingly defeated in the Lords, and the following month Salisbury was returned for another ministry.

After the Conservative defeat in 1892, Ritchie's retirement made Long the chief opposition spokesman on local government, and when the Tories returned to power in 1895, he entered the cabinet as President of the Board of Agriculture. In this role he was notable for his efforts to prevent the spread of rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. Early symptoms can include fever and tingling at the site of exposure. These symptoms are followed by one or more of the following symptoms: nausea, vomiting, vi ...

. The creation of the Board of Agriculture had brought a boost to Long's career in 1889. But opposition rose up strongly, when the Dog Muzzlers act, prompted the Laymen's League in Liverpool to contest the Church discipline bill. Long became increasingly unpopular in his constituency accused of being "irascible and scheming", and was advised to change seats. But this did not prevent in 1895 admittance to the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

. The bourgeois Navy League in Liverpool could not wait to get rid of him but his powerful friends, like the "somnolent" Duke of Devonshire gave large donations to the Anti-Socialist Union - and this would be disastrous to the Union, for it would immediately alienate every snob and mediocrity ..." Yet Long was thick-skinned and seems impervious to the insults, for he remained remarkably successful at the polls.

At the 'Khaki election' of November 1900, Long won Bristol South

Bristol South is a List of United Kingdom Parliament constituencies, constituency represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, UK Parliament since 2015 United Kingdom genera ...

. With the ministerial shuffle in 1900, he became President of the Local Government Board The President of the Local Government Board was a ministerial post, frequently a Cabinet position, in the United Kingdom, established in 1871. The Local Government Board itself was established in 1871 and took over supervisory functions from the ...

. Never an insider, Long worked closely with constituents on local issues showing "sensitivity to the wider needs of society". His capacity for hard work revealed that he was also stubborn, short-tempered, with a choleric temperament; a stickler for the letter of the law. He was frequently plagued by ill-health: neuralgia

Neuralgia (Greek ''neuron'', "nerve" + ''algos'', "pain") is pain in the distribution of one or more nerves, as in intercostal neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Classification

Under the general heading of neuralg ...

, arthritis

Arthritis is a term often used to mean any disorder that affects joints. Symptoms generally include joint pain and stiffness. Other symptoms may include redness, warmth, swelling, and decreased range of motion of the affected joints. In som ...

, susceptible to colds and flu

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptom ...

; a waspish character, he was not charismatic, nor was he analytic or probing, like his mentor Balfour. In this role, he was criticised as too radical for his support of the Unemployed Workmen's Act 1905, which created an unemployment board to give work and training to the unemployed.

In 1903, Long took a leading role as a spokesman for the protectionist wing of the party, advocating tariff reform and imperial preference alongside Joseph Chamberlain

Joseph Chamberlain (8 July 1836 – 2 July 1914) was a British statesman who was first a radical Liberal, then a Liberal Unionist after opposing home rule for Ireland, and eventually served as a leading imperialist in coalition with the Cons ...

and his son Austen Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

, which brought him into conflict with Charles Ritchie, Michael Hicks-Beach and others on the free-trade wing. Long was a moderate within the protectionist ranks and became a go-between for the protectionists and free-traders, increasing his prominence and popularity within the party. Perhaps his most significant achievement on the board was the unification of the London water-supply boards into the Metropolitan Water Board

The Metropolitan Water Board was a municipal body formed in 1903 to manage the water supply in London, UK. The members of the board were nominated by the local authorities within its area of supply. In 1904 it took over the water supply functi ...

.

Chief Secretary for Ireland

Long was offered the position ofFirst Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

in Lord Selborne

Earl of Selborne, in the County of Southampton, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1882 for the lawyer and Liberal politician Roundell Palmer, 1st Baron Selborne, along with the subsidiary title of Viscount Wo ...

's place, as the latter was appointed to the Governor-Generalship of South Africa. But he refused the promotion, advising the appointment of Lord Cawdor. Really what Long wanted was to remain at Local Government, but when George Wyndham

George Wyndham, PC (29 August 1863 – 8 June 1913) was a British Conservative politician, statesman, man of letters, and one of The Souls.

Background and education

Wyndham was the elder son of the Honourable Percy Wyndham, third son of Ge ...

resigned as Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant", from the early 19th century un ...

, Balfour was faced with a crisis. Wyndham resigned on 5 March 1905, over what became known as the "Wyndham-MacDonnell Imbroglio".

Sir Antony MacDonnell was a successful Indian civil servant appointed as administrator in Dublin by Wyndham, on the strict understanding that the permanent post made MacDonnell's role a non-political position. MacDonnell was a Catholic from Mayo Mayo often refers to:

* Mayonnaise, often shortened to "mayo"

* Mayo Clinic, a medical center in Rochester, Minnesota, United States

Mayo may also refer to:

Places

Antarctica

* Mayo Peak, Marie Byrd Land

Australia

* Division of Mayo, an Aust ...

, whose appointment left unionists wondering if they had been betrayed by London. Nevertheless, having been an experienced and competent implementer of the Land Purchase (Ireland) Act 1903

The Land Acts (officially Land Law (Ireland) Acts) were a series of measures to deal with the question of tenancy contracts and peasant proprietorship of land in Ireland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Five such acts were introduced by ...

, MacDonnell came to be widely seen as a force for moderation. Wyndham was occupied in London with cabinet duties, and so appreciated the implied need for permanent governance. Balfour had already considered Long for the post in January 1905, and to that end consulted both Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who served as the Attorney General and Solicito ...

and John Atkinson under pressure from Horace Plunkett

Sir Horace Curzon Plunkett (24 October 1854 – 26 March 1932), was an Anglo-Irish agricultural reformer, pioneer of agricultural cooperatives, Unionist MP, supporter of Home Rule, Irish Senator and author.

Plunkett, a younger brother of Jo ...

and Gerald Balfour, to continue the policy of moderate reform. Due to his Irish connections (both his wife and his mother were Irish), it was hoped that Long might be more acceptable to Irish Unionists than his predecessor.

Long was reluctant to accept the offer; frustrated and angered by Lord Dunraven's proposals and MacDonnell's initiatives that he regarded as anti-Unionist. In mid-March he was determined to bring Unionism back from the brink of extinction in Ireland. Arriving in Dublin on 15 March, at dinner there he took the pragmatic view to work with MacDonnell. Throughout March and April he saw no grounds for MacDonnell's dismissal. Yet labouring closely with Unionists to discuss agrarian and non-agrarian crime, and discipline in the RIC, he continued to appease Unionist opinion. He appointed Unionists William Moore as Solicitor-General for Ireland, John Atkinson, as Lord of Appeal, while Edward Saunderson

Colonel Edward James Saunderson (1 October 183721 October 1906) was an Anglo-Irish landowner and prominent Irish unionist politician. He led the Irish Unionist Alliance between 1891 and 1906.

Early life

Saunderson was born at the family seat ...

, the Ulsterite member of the Orange Order

The Loyal Orange Institution, commonly known as the Orange Order, is an international Protestant fraternal order based in Northern Ireland and primarily associated with Ulster Protestants, particularly those of Ulster Scots heritage. It also ...

, became a confidant and close friend. Patronage was usually dispensed by the Lord Lieutenant: this sparked a row with Lord Dudley, and a constitutional argument prompted an appeal to the Prime Minister. Long's motto of "patience and firmness" was designed to placate Irish Unionists at public meetings, speeches and tours of Ireland, made to reassure local community officials.

On 20 April 1905, he made an important speech at Belfast emphasizing that he was a stickler for order and the rule of law. But in the south and west, obdurate landlords refused land sales to tenantry leading to boycotts and cattle-driving. The damage done to unionist farms and farmers was frightening. MacDonnell continually urged compromise, but Long ignored him. The dispute with Lords Dudley and Dunraven dragged on into August 1905, with their attitude of intransigence towards Long's attempts at Unionist reform, and obedience to the law. On 25 May 1905, the issues were discussed in the Commons. He wished to strengthen Unionism; but both Dudley and Long appealed to Balfour for adjudication. Balfour opined that the Chief Secretary was both in the Commons and in the cabinet so Dudley had to be content that the power of the Lords was waning. During the last quarter of 1905, Long advised the postponement of dissolution, as it would hit Unionists hard in "the Country" and would hand numerous electorates to radicals. He warned of the loss of seats of Bristol West and South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

. In December 1905, true to his word, he himself was defeated by 2,692 votes. Long continued to distrust 'Birmingham & Co' as he called Chamberlain

Chamberlain may refer to:

Profession

*Chamberlain (office), the officer in charge of managing the household of a sovereign or other noble figure

People

*Chamberlain (surname)

**Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1927), German-British philosop ...

's struggle for a policy of Tariff recognition, which was already driving the party away from the Free Trade north. Nonetheless, he continued to co-operate transnationally with conservative parties in Germany, such as Reichspartei right up until the second Moroccan crisis in 1911.

Unionist in opposition

Nonetheless, Long's parliamentary career was far from finished. He was nominated as Unionist candidate forSouth Dublin

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map South Dublin.svg

, map_caption = Inset showing South Dublin (darkest green in inset) within Dublin Region (lighter green)

, area_total_km2 ...

in 1906, winning by 1,343 votes. Long became one of the leading opposition voices against the Liberal plans for Home Rule in Ireland. At this stage the Irish Unionist Party's leadership was still in the hands of his friend Edward Saunderson, who was far from energetic, unhelpfully described as "devoid of business capacity".

The dispute with MacDonnell was carried on in the pages of ''The Times'' - Long trying to galvanise Unionist opinion in both England and Ireland. Balfour, Jack Sandars (Balfour's private secretary), and Wyndham all thought he had been duped by Unionism "where his vanity and hopes are concerned", characterising the Chief Secretary as easily manipulated. In October 1906, Saunderson died, and Long was chosen as the new Chairman of Irish Unionist Alliance

The Irish Unionist Alliance (IUA), also known as the Irish Unionist Party, Irish Unionists or simply the Unionists, was a unionist political party founded in Ireland in 1891 from a merger of the Irish Conservative Party and the Irish Loyal and ...

(IUA) - aimed at closer co-operation between northern and southern parties. Three months later, he was also elected as Chairman of the Ulster Unionist Council

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

(UUC). In 1907, he formed the Union Defence League (UDL) as a support in Great Britain for Irish unionism. The UDL in London linked with the UUC in Belfast and the IUA in Dublin. It had support from Conservative backbenchers but not the leadership. It was active in 1907–1908 and again after 1911 when the Third Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act of Parliament, Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home ...

was imminent; with the Primrose League

The Primrose League was an organisation for spreading Conservative principles in Great Britain. It was founded in 1883.

At a late point in its existence, its declared aims (published in the ''Primrose League Gazette'', vol. 83, no. 2, March/April ...

it created the 1914 British Covenant The British Covenant was a protest organised in 1914 against the Third Home Rule Bill for Ireland. It largely mirrored the Ulster Covenant of 1912.

With the failure of Asquith and Bonar Law to reach a compromise on the delayed bill, Law accepted t ...

mirroring the 1912 Ulster Covenant

Ulster's Solemn League and Covenant, commonly known as the Ulster Covenant, was signed by nearly 500,000 people on and before 28 September 1912, in protest against the Third Home Rule Bill introduced by the British Government in the same year.

...

. Although Long never openly supported the most militant Unionists, who were prepared to fight the Southern nationalists (and perhaps the British Army) to prevent home rule for Ireland, contemporary accounts indicate that he probably had prior knowledge of the Larne gunrunning

The Larne gun-running was a major gun smuggling operation organised in April 1914 in Ireland by Major Frederick H. Crawford and Captain Wilfrid Spender for the Ulster Unionist Council to equip the Ulster Volunteer Force. The operation involved t ...

.

In the Commons Walter Long was an active opponent of Liberal social legislation. He founded a Budget Protest League to advance the cause of moderate tax changes. In the Lords the defeat of the 'people's budget' led to the constitutional crisis of 1911. He clashed with Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who served as the Attorney General and Solicito ...

adopting a similarly equivocal position over the Parliament Bill of 1911, opposing the Bill, but recommending acquiescence. He sat as MP for the Strand

Strand may refer to:

Topography

*The flat area of land bordering a body of water, a:

** Beach

** Shoreline

* Strand swamp, a type of swamp habitat in Florida

Places Africa

* Strand, Western Cape, a seaside town in South Africa

* Strand Street ...

between December 1910 and 1918 and St George's between 1918 and 1921.

Political career, 1911–1921

When Balfour resigned as party leader in November 1911, Long, who had never been happy with his leadership style, was pre-eminent in the Conservative Party and one of the leading candidates to succeed him, the candidate of the 'country party'. As early as 1900, Long had denounced Chamberlain, as the "Conservative Party...will not be led by a bloody radical". However, he was opposed byAusten Chamberlain

Sir Joseph Austen Chamberlain (16 October 1863 – 16 March 1937) was a British statesman, son of Joseph Chamberlain and older half-brother of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He served as Chancellor of the Exchequer (twice) and was briefly ...

, who was backed by the Liberal Unionists

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

still under his father's leadership. Long feared 'the degradation' to the party that a divisive contest might split the protectionist majority of the Unionist coalition, so both candidates agreed to withdraw in favour of Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law ( ; 16 September 1858 – 30 October 1923) was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from October 1922 to May 1923.

Law was born in the British colony of New Brunswick (now a ...

, the ''tertium quid'', and a relatively unknown figure, on 12 November.

The unification of the Liberal Unionist and Conservative parties at the Carlton Club in 1912, was for Long acknowledgement of the end of its domination by the country interest. Long was always skeptical of coalition, and declared that it would not happen. So with the formation of the wartime coalition government in May 1915, Long's awaited return to office at the Local Government Board was greeted by his surprise. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party (UK), Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of ...

resisted attempts by Unionists to install Long as Chief Secretary. Long dealt with the plight of thousands of Belgian refugees. He was actively involved in undermining attempts by Lloyd George to negotiate a deal between Irish Nationalists and Unionists in July 1916 over introducing the suspended Home Rule Act 1914

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home rule (self-governm ...

, publicly clashing with his arch-rival Sir Edward Carson

Edward Henry Carson, 1st Baron Carson, PC, PC (Ire) (9 February 1854 – 22 October 1935), from 1900 to 1921 known as Sir Edward Carson, was an Irish unionist politician, barrister and judge, who served as the Attorney General and Solicitor ...

. He was accused of plotting to bring down Carson by jeopardising an agreement with the nationalist leader John Redmond

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalism, Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as lead ...

, that any partition would only be temporary. When Long wanted to alter the clause to permanent, Redmond abandoned further negotiations. Carson, in a bitter riposte, said of Long "The worst of Walter Long is that he never knows what he wants, but is always intriguing to get it". Austen Chamberlain, in 1911, was similarly critical of Long, saying he was "at the centre of every coterie of grumblers."

Long and the Unionists wanted General Maxwell to have authority over the police, but Asquith finally gave the Chief Secretaryship to a civilian, Henry Duke. With the fall of Asquith and the accession of the Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party (United Kingdom), Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for lea ...

government in December 1916, Long had established himself as the cabinet's foremost authority on Irish policy. Chief Secretary Duke would have preferred to be Inspector-General; but Lloyd George, a natural home ruler, did not seem too happy with Long's brand of federated Unionism. Two allies of the Prime Minister, namely Carson and Lord Edward Cecil

Lord Edward Herbert Gascoyne-Cecil (12 July 1867 – 13 December 1918), known as Lord Edward Cecil, was a distinguished and highly decorated English soldier. As colonial administrator in Egypt and advisor to the Liberal government, he helped t ...

, supplied the most intransigent opposition to a united Ireland.

It was Long's policy on 16 April 1918 to promote the Conscription bill that would provoke the crisis for Irishness. Duke opposed a policy of conscription without an offer of home rule, whereas Long wanted the former without the latter. The crisis gave rise to the German Plot, and Long's pressure to act on intelligence against Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

ers caused him to issue a large number of arrest warrants.

Long was promoted to the Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of col ...

, serving until January 1919, when he became First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

, a position in which he served until his retirement to the Lords in 1921. From October 1919 on, he was, once again, largely concerned with Irish affairs, serving as the chair of the cabinet's ''Long Committee'' on Ireland. In this capacity, he was largely responsible for initiating the Partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. I ...

under the Government of Ireland Act 1920

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 (10 & 11 Geo. 5 c. 67) was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. The Act's long title was "An Act to provide for the better government of Ireland"; it is also known as the Fourth Home Rule Bill ...

, which followed certain proposals of Lloyd George's failed 1917–18 Irish Convention

The Irish Convention was an assembly which sat in Dublin, Ireland from July 1917 until March 1918 to address the ''Irish question'' and other constitutional problems relating to an early enactment of self-government for Ireland, to debate its wid ...

, and created separate home rule governments for Southern Ireland

Southern Ireland, South Ireland or South of Ireland may refer to:

*The southern part of the island of Ireland

*Southern Ireland (1921–1922), a former constituent part of the United Kingdom

*Republic of Ireland, which is sometimes referred to as ...

and Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, the former subsequently evolving as the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between th ...

.

In March 1921, Bonar Law resigned as party leader due to ill-health. Sir Austen Chamberlain finally succeeded him in the former office after a ten-year wait. But Long too, getting tired and old, was 'kicked upstairs' with a peerage. He was appointed Lord-Lieutenant of Wiltshire

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ...

in February 1920, and was raised to the peerage as Viscount Long

__NOTOC__

Viscount Long, of Wraxall in the County of Wiltshire, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.

It was created in 1921 for the Conservative politician Walter Long, who had previously served as Member of Parliament, Presiden ...

, of Wraxall in the County of Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

, in May 1921.''The Times'' (Monday, 23 May 1921, p. 10); (Tuesday, 31 May 1921, p. 10).

Personal life

Lord Long married Lady Dorothy (Doreen) Blanche, daughter of the 9th Earl of Cork and Orrery, in 1878. They had two sons, including Brigadier General Walter Long, who was killed in action in 1917, and three daughters. He died at his home,Rood Ashton House

Rood Ashton House was a country house in Wiltshire, England, standing in parkland northeast of the village of West Ashton, near Trowbridge. Built in 1808 for Richard Godolphin Long, it was later the home of the 1st Viscount Long (1854–1924).

...

in Wiltshire, in September 1924, aged 70, and was succeeded by his 13-year-old grandson Walter

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 19 ...

. Lady Long died in June 1938.

Bibliography

Writings

* Long, Viscount Walter Hume, ''Memories'' (London 1923)Primary sources

* * * * * * * * * * *Secondary sources

* * * * * * * * *References

Further reading

Inheriting the Earth: The Long Family's 500 Year Reign in Wiltshire; Cheryl Nicol

at longfamilyofwiltshire.webs.com

External links

*Photograph in the National Portrait Gallery

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Long, Walter Hume 1854 births 1924 deaths People educated at Harrow School Alumni of Christ Church, Oxford Long, Walter Hume, 1st Viscount Long Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies First Lords of the Admiralty Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Dublin constituencies (1801–1922) British Secretaries of State Irish Unionist Party MPs Irish Anglicans UK MPs 1880–1885 UK MPs 1885–1886 UK MPs 1886–1892 UK MPs 1892–1895 UK MPs 1895–1900 UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910 UK MPs 1910–1918 UK MPs 1918–1922 UK MPs who were granted peerages Deputy Lieutenants of Wiltshire Lord-Lieutenants of Wiltshire Presidents of the Marylebone Cricket Club

Walter

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 19 ...

People from Trowbridge

Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for Liverpool constituencies

Fellows of the Royal Society

Directors of the Great Western Railway

Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

Members of the Privy Council of Ireland

Chief Secretaries for Ireland

Secretaries of State for the Colonies

Irish Conservative Party MPs

Viscounts created by George V